On shooting for free

09/07/12 22:15 Filed in: Business

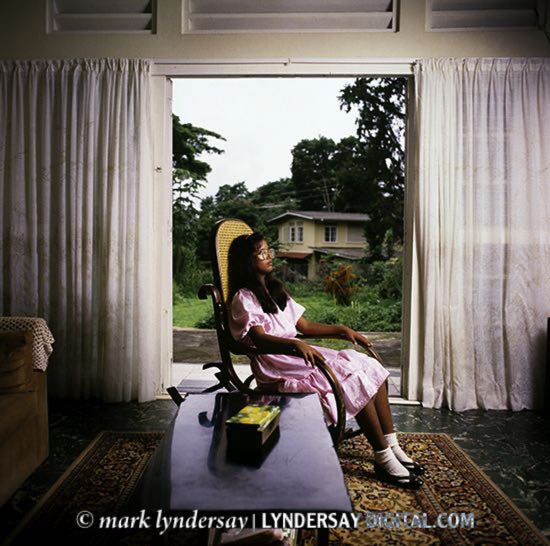

A young child living with Down's Syndrome, photographed at her home in late 1988 for the National Down's Syndrome Association's calendar for 1989. Photograph by Mark Lyndersay and yes, that's James McNeil Whistler I'm channelling there.

The project was shot on 6x6 black and white film, but I did a couple of rolls of medium format transparencies to offer to the Guardian, which was publishing my color work regularly in their Sunday magazine back then.

Free isn’t necessarily a bad thing, and I have to tell you, it’s way better than cheap.

For many years, when I began my career in 1978, I photographed the theatre. I shot stage productions, backstage, portraits both formal and informal and built quite a reputation as a photographer capable of handling black and white photography.

I did all this either at my own cost, for most of the first five years or with the production companies underwriting the costs of film, chemistry and photographic paper (usually given as a donation to the producers) for the work to get done. Free shouldn’t mean that you spend to do a job, and that stuff was expensive.

I learned a lot doing this work. I learned to soup black and white film in rare chemistries like Diafine to push the emulsions to their absolute limit. I learned to handle small flashes in location and studio style lighting under odd and often pressured situations. One of my very first location portrait shoots was done in the half an hour before a production began at the Little Carib Theatre. People were filing in to take their seats while I was putting away the 611 hammer style flashes I worked with back then.

The beginnings of my craft as a portrait photographer began with the lobby portraits I began doing for productions by Helen Camps’ All Theatre Productions and the Tent Theatre project that followed it.

It was a lot of fun until it stopped being fun, and then I stopped doing it. That work left me with a decade’s worth of photographs of a theatre and it's practitioners in transition from one era to another. Stanley Marshall and Errol Jones in their prime, a young Raymond Choo Kong and Cecelia Salazar.

It took a long time, but eventually I began to understand that my photography had value and the work I was putting into it should have a price, even if it wasn’t actually getting paid in cash on some projects. While I was giving it away, I wasn’t selling it cheaply and the difference between the two would, over time, be a world of difference. I hear of theatre companies today demanding copyright for photography they can't afford and all I can manage, as the young people put it, is a rueful smh.

By 1988, I’d really begun to understand the score. The National Association for Down's Syndrome contacted me about photographing a calendar for them featuring some of the children they worked with.

I thought it was a great idea, but I thought they way they wanted to go about it was wrong for the subject.

The NADS folks wanted to bring the children to the studio. I though that wouldn't read well as photographs and would fix attention on the physical characteristics common to such children.

These were young people who had lives and families and much of their story was about just how special those relationships were.

Those were the photographs I wanted to make. We disagreed on this point, and it was on this project that I formulated the methodology that I’ve used ever since to govern my decisions about such projects.

I’d do whatever they wanted, but they would pay my price, because that makes it a job. Or…I would do it for free and they would do it the way I wanted. I offered a quotation. We did it my way.

The 1989 NADS calendar remains one of those projects I’m remained proud of over the decades. I shot at 14 locations, capturing children at their homes, with their families, in environments in which they were comfortable and I was a guest.

Designer Russel Halfhide, famous for his defining work on Caribbean Beat, pitched in to design the piece and asked some of the children to write numbers, which he used for the calendar dates.

Most recently I had an excellent opportunity to work with ALTA, the local adult literacy organization, who had asked about getting some work done. It’s certainly started well with the first project, a poster. I'm a reader as well as a writer, so a project that opens up the world of words to people runs close to my heart.

It arrived at a difficult time for me, so I was willing to just follow orders on this one and asked for a brief from the agency who was supposed to be doing the artwork.

That didn’t happen, but the back stories on the three models were so fascinating that the images suggested themselves, as did the caption copy that goes along with them, which I wrote and offered to the organization.

On an ongoing basis, I continue to contribute work to the Trinidad Guardian, working there for an absurdly low rate, which also happens to be the very top of their pay scale. The leveraging difference for me on those projects, which include Local Lives, is the value of publication in a widely read newspaper and the satisfaction that I personally get from keeping my hand in photojournalism (I've been in charge of photographic departments at three different local daily newspapers), albeit at more of a distance.

Free then, as you’ll also read here is a challenging way to market your work and find satisfaction, but it can be fulfilling it as well if you think through your involvement (and investment) carefully and plan your participation sensibly.

blog comments powered by Disqus