Everything I know about Ian Alvarez I learned from Bunji Garlin

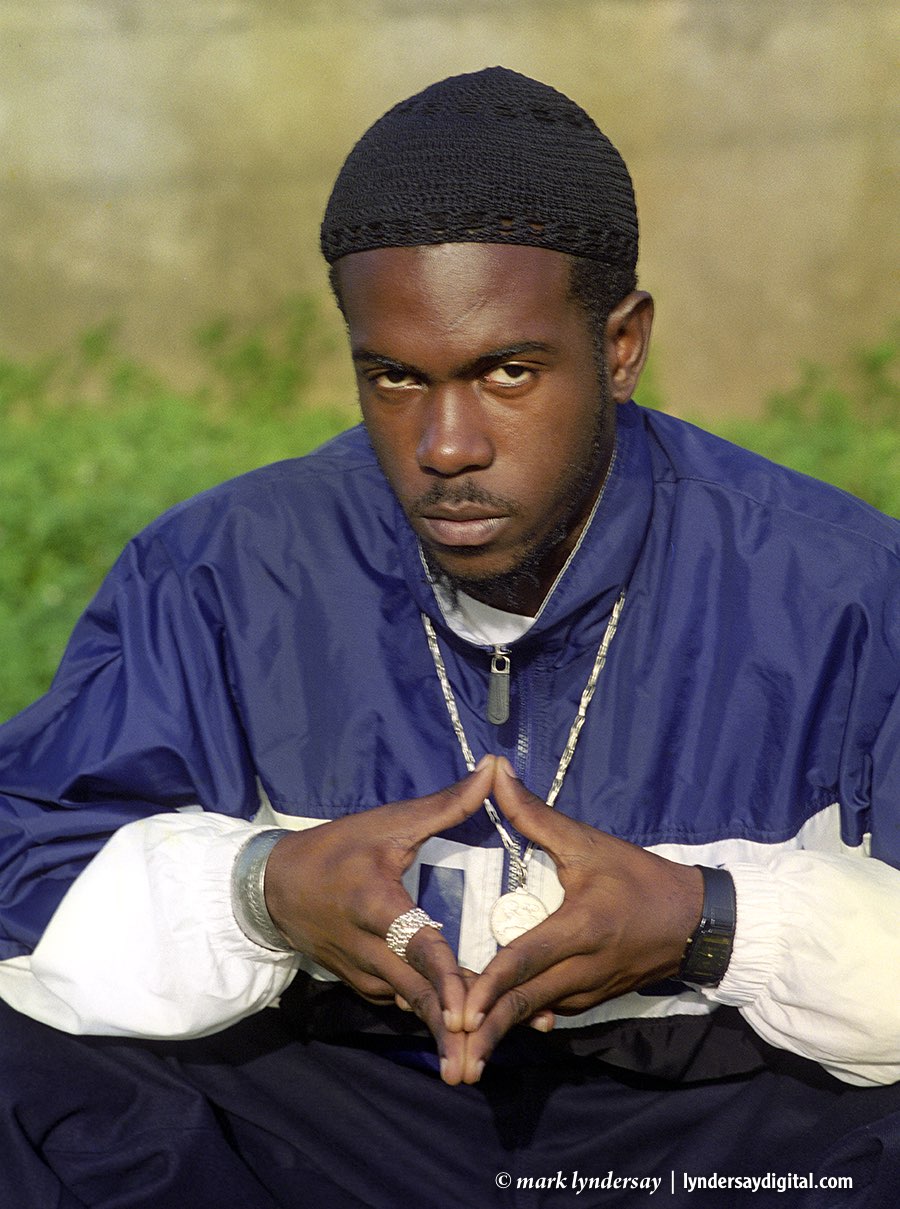

Bunji Garlin photographed in 1996 for the compilation CD New Vibes, produced by Rituals Records. Photo by Mark Lyndersay.

Originally published in the January/February 2015 issue of Caribbean Beat.

In the year 2000, when all the conversations were about the millennium bug, and technology remained more than a little frightening and indecipherable, Bunji Garlin, born Ian Alvarez from Sangre Grande, made me think again of the very first crossover calypso song, Lord Shorty’s Soca Vibrations.

Specifically, the very first word of that song’s lyric, “Change,” left hanging for a beat by Shorty as if to give the listener a chance to really consider everything that was to come.

What followed for the calypsonian was a decade-long struggle between the well-defined forms of traditional calypso and soca, an upstart merging of the R&B and funk that commanded the airwaves between Carnival seasons in Trinidad and Tobago.

At 22, Alvarez took up the mantle left behind by Shorty, and began to push the process of assimilating popular music in all directions, crossing over everywhere.

Bunji Garlin, a name he adopted to marry the flexibility of the cable with the firepower of the weapon (possibly a street corruption of Galil), performed under the temporary mantle of raggasoca, a provisional hybrid of reggae, rap and soca.

But Alvarez embraced far more than the early definitions of the form.

His collaborations from the start were prolific and pervasive. His distinctive voice, which has evolved from a thick faux Jamaican drawl into something uniquely Trinidadian and clearly evocative of the West Indies, appears on dozens of compilations.

He collaborates down, across and upward, performing with protest calypsonian Singing Sandra (Coofy Lie Lie), lending gravitas to Shammi's lightweight chutney contender Soca Bhangra and more decisively with Hunter on Bring it.

His other duets with artists include Busy Signal, Rupee, Edwin Yearwood, Skinny Fabulous, 3 Suns, Neshan Prabhoo, Diplo, Shurwayne Winchester and most recently Kid Ink and Chris Brown on Main Chick.

The first time I met Alvarez was on a sunny afternoon in 1996 to photograph him and performing partner Ninja Kat for New Vibes, a compilation of new music in the emerging scene produced by Rituals Music. The largely forgettable song, Look Behind, is typical of much of his early work.

The rapidfire chanting collides with shambling music that simply isn’t up to his ambitions.

I'd first heard Alvarez working at audio engineer Robin Foster's Maraval studio where he was putting down tracks for a collaboration with Ital-D.

Foster remembers being impressed even then with the imagery of his words and describes those skills as exceptional.

In 2000, the young artist dropped a stunning five songs, rocking the Carnival season.

There was the brooding admonishing of Bad Man, which laments a woman’s poor choices in partners, Breakaway, Gimme the Brass and Send them Riddem Crazy, which all targeted the season's parties were he would be in constant demand to perform and the one song that I kept on repeat for days, the one that signalled most clearly how bold a musician Alvarez really was.

Woman was a casual collaboration with singer and guitarist Walker, who had performed with Machel Montano previously.

Over a loping beat he trades lines with the American singer who warns “Don’t turn your back on that woman,” while Alvarez peppers the song with street savvy relationship warnings.

Like most overnight successes, the explosion of the artist known as Bunji Garlin on music charts internationally in summer 2013 with Differentology was the result of a remarkably prolific career that took root in that seminal collection of songs during Carnival 2000.

Over the next 14 years, Alvarez would release more than a hundred songs that remain poorly collected and diffused across an box load of compilation albums.

There are currently four officially available Bunji Garlin albums and the recent EP Carnival Tabanca.

The indifferently recorded Revelation collects several seminal songs, including the party focused Send dem Riddem Crazy, the blisteringly anti-rapist song Licks, and the proudly declarative In the Ghetto, a mission statement for his generation’s influences and perspective.

On that album you’ll also find the gospel driven God is not far and an ambivalent return engagement with Walker on Marvin Gaye’s Let’s get it on.

Global, released in 2007, more determinedly sought international attention, featuring collaborations with TOK, Rita Jones, Chris Black and Freddie MacGregor, but it jumps around erratically, juxtaposing straight ahead soca with crossover reggae performances.

iSpaniard, released in 2012, reflects the work of a far more mature and focused artist.

This is the album that confidently collects works that are more clearly designed for the evolving Carnival festival, the bouncy Tun Up, the driving Cosmic Shift, the groovy soca anthem Runaway, recorded with Kerwyn Du Bois, and Gift of Soca, with a frisson of guitar strumming that presages Differentology.

It's here that he stakes his claim on the soca landscape and his responsibility in developing it.

“Is like a sword in me hand given down by God and I know how to use it,” he sings on Gift of Soca. “Them say soca music will never see the Grammy awards, I don’t really care about that, we was here before the Grammy awards. I don’t need no foreign entity, to validate my identity.”

Accolades from foreign entities came in a sudden rush in 2013 for the stolid Alvarez anyway. Grey’s Anatomy prominently featured the breakthrough hit Differentology on a widely seen episode, and he won the Soul Train award for Best International Performance.

That led to the mid-year release of a supporting album, Differentology, featuring nine strong songs in support of his groundbreaking collaboration with local rock star Nigel Rojas, whose Spanish guitar intro lit the slow burn of the hit song.

A remake of Maestro’s Savage, the delicate lament Carnival Tabanca and the darkly fascinating Red Light District bouyed that album to well-deserved success, though the last four songs were pure filler and two remixes on an album is always a suspect move.

Biographies of Bunji Garlin tend to skip forward from his early successes in Carnival competitions in Trinidad and Tobago, where he won the RaggaSoca Monarch competition twice, his Young King win and his four triumphs in the International Soca Monarch competition to the Differentology era.

But over that 14 years, there have been three distinct phases in the development of Ian Alvarez.

The first finds the young performer calmly exploding on the local soca scene, handsome, deep-voiced, gentlemanly and dreadlocked. The courtly performer was lauded as “the girl’s them darling."

Then there is the Faye-Ann Lyons era, which quickly evolved from two popular artists dating into a robust personal collaboration that led to conflicts with first Lyons’ band and then Alvarez’s management.

The couple, who married in 2006 and have a child together, weathered all the fuss and anyone who has seen them perform together knows why.

On a stage, they trade courtesies, Alvarez is a supportive and admiring presence when his wife, a considerable soca and road march star in her own right performs and Lyons, in turn, is his staunch and flinty defender.

In Trinidad and Tobago, there’s a homily that warns that two people can’t climb a ladder together.

As the two have worked together, they have offered a remarkable model for cooperation and mutual support that's rare in the local industry.

Finally, there is the era of the Godfather’s Asylum Band, which has fundamentally redefined Alvarez’s approach by giving him a laboratory where he can experiment with music with like-minded souls. The group’s St James studio space is like an extended family meeting spot, and it’s here that wild ideas like the delicately symphonic piano bed that lends a bitterly wistful atmosphere to Carnival Tabanca get worked out.

If there’s anything that remains to be done by Ian Alvarez, it’s to think about his work in the context of an album and not the collection of the singles he’s been producing all his life.

In many ways, he is an artist of this century and very much of this time and musically, this is the era of the four-minute single.

His songs respond to sudden shifts in mood and style mercurially, often presaging tastes before they are fully formed.

He’s ridden uncounted rhythms crafted by others, collaborated with dozens of artists, but has enjoyed his greatest successes when he tackles subjects that are closest to his heart and works with people whose craft he can encircle and embrace.

The breathless urgency of the vocal on Differentology was driven by Nigel Rojas’ inspired playing, the keening vocal of Carnival Tabanca, a clear response to the keyboard work of Sherrif Mumbles, his music band captain.

As remarkable as the century has been for Bunji Garlin, it all feels like a prelude to the work he's creating now.