Errol Jones

25/06/10 10:30 Filed in: Obituary

On losing our master actor

by Mark Lyndersay

Originally published in the Trinidad Guardian, June 25, 2010

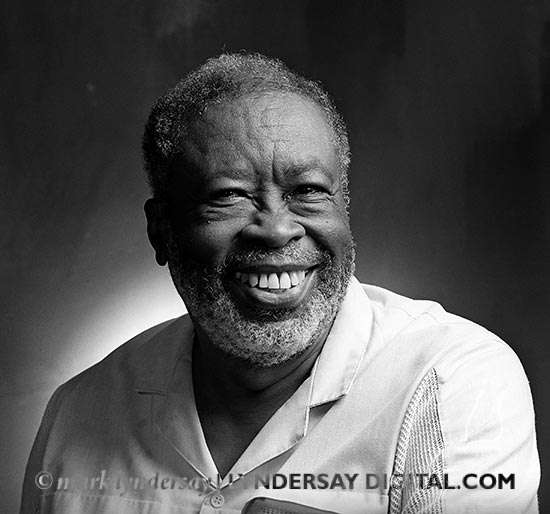

Errol Jones photographed at a casting call of the Trinidad Theatre Workshop in the mid-1990's. Photograph by Mark Lyndersay.

Beyond the loss of his enormous talent, the true tragedy of Errol Jones' passing is that so few of today's fans of Trinidad and Tobago theatre have ever seen him work.

His was an unforgettable presence on the stage. A big man with a rich, booming voice and the most generous and engaging smile I've ever seen.

In one of his most remarkable performances (in Helen Camps' production of Athol Fugard's Sizwe Bansi is Dead), he played a humble, confused South African man wrestling with the emasculation of apartheid, he seemed to shrink into an ill-fitting suit, muted his voice to a whisper and became an entirely persuasive mouse ill-at-ease in a man's body.

In one of his most remarkable performances (in Helen Camps' production of Athol Fugard's Sizwe Bansi is Dead), he played a humble, confused South African man wrestling with the emasculation of apartheid, he seemed to shrink into an ill-fitting suit, muted his voice to a whisper and became an entirely persuasive mouse ill-at-ease in a man's body.

Jones was already in the twilight of his career when I met him more than three decades ago. An inspiringly mature actor, he traded up from youthful physicality to expressive nuance, offering, for instance, a cocked eyebrow and squared shoulders more eloquent than the shameless mugging that his juniors indulged in.

As local theatre was overwhelmed by bolder, more comedic performances, there was less and less room for the work of the Trinidad Theatre Workshop, the group that Jones worked with for much of his life and career and consequently, there was that much less room for him.

Errol Jones had been a friend to my family, often hanging out with my father and mother along with his friend Russel Celestine in the home I live in today.

I’ll always remember him for the dignity he afforded my early efforts with the theatre, asking me just once if my father was Dexter and never referring to me, as so many of his colleagues did, as “young Lyndersay.”

He could allow me to be my own man, I think, because he was so very much his own, sure and secure in his abilities, robust in his work.

In some ways, he was the right actor at the wrong time. His best work went unrecorded in an era when local productions were rarely taped and his gregarious beauty was the wrong cut for the local television of the time.

He should have been our James Earl, but for those of us who had a chance to see him when he trod the boards of local theatre, he was the fulfilment of local acting expertise. Jones in performance was more often than not the best thing on the stage, better most of his cast mates by leagues, his presence larger than the faltering lighting of the times and his voice more commanding than the words he was often given to speak.

He should have been our James Earl, but for those of us who had a chance to see him when he trod the boards of local theatre, he was the fulfilment of local acting expertise. Jones in performance was more often than not the best thing on the stage, better most of his cast mates by leagues, his presence larger than the faltering lighting of the times and his voice more commanding than the words he was often given to speak.

It’s no coincidence that his best work was done with Derek Walcott when that playwright and poet led the workshop, and the deft turns of phrase and delicate witticisms gave him material to work with that challenged him.

For those who had the opportunity to see him work, it’s safe to say that we will rarely see his like in local theatre again, for those who never did, there aren’t words to explain what you missed.

by Mark Lyndersay

Originally published in the Trinidad Guardian, June 25, 2010

Errol Jones photographed at a casting call of the Trinidad Theatre Workshop in the mid-1990's. Photograph by Mark Lyndersay.

Beyond the loss of his enormous talent, the true tragedy of Errol Jones' passing is that so few of today's fans of Trinidad and Tobago theatre have ever seen him work.

His was an unforgettable presence on the stage. A big man with a rich, booming voice and the most generous and engaging smile I've ever seen.

Jones was already in the twilight of his career when I met him more than three decades ago. An inspiringly mature actor, he traded up from youthful physicality to expressive nuance, offering, for instance, a cocked eyebrow and squared shoulders more eloquent than the shameless mugging that his juniors indulged in.

As local theatre was overwhelmed by bolder, more comedic performances, there was less and less room for the work of the Trinidad Theatre Workshop, the group that Jones worked with for much of his life and career and consequently, there was that much less room for him.

Errol Jones had been a friend to my family, often hanging out with my father and mother along with his friend Russel Celestine in the home I live in today.

I’ll always remember him for the dignity he afforded my early efforts with the theatre, asking me just once if my father was Dexter and never referring to me, as so many of his colleagues did, as “young Lyndersay.”

He could allow me to be my own man, I think, because he was so very much his own, sure and secure in his abilities, robust in his work.

In some ways, he was the right actor at the wrong time. His best work went unrecorded in an era when local productions were rarely taped and his gregarious beauty was the wrong cut for the local television of the time.

It’s no coincidence that his best work was done with Derek Walcott when that playwright and poet led the workshop, and the deft turns of phrase and delicate witticisms gave him material to work with that challenged him.

For those who had the opportunity to see him work, it’s safe to say that we will rarely see his like in local theatre again, for those who never did, there aren’t words to explain what you missed.

blog comments powered by Disqus