Review of Days of Wrath

28/07/08 20:11 Filed in: Reviews

Days of Wrath

The 1990 Coup on Trinidad and Tobago

Raoul A Pantin

Photography and review by Mark Lyndersay, published in the May 2008 issue of the Caribbean Review of Books.

There’s a popular argument that the coup attempt in Trinidad and Tobago changed this twin-island nation forever, that the growth of violent crime over the last decade can be traced back to that act of pointless lawlessness and the distribution of guns on the evening of July 27, 1990.

But the actions of Imam Abu Bakr and his followers actually impacted directly on a relatively small sliver of the nation's population.

It's possible that no more than two thousand people were directly engaged in the events of the six days of fear and uncertainty that the insurrectionist Muslimeen brought to the Red House and TTT in the name of Islam and with the stated purpose of overthrowing the lawful government of Trinidad and Tobago.

Among that number I count the looters who pillaged Port of Spain, the police officers, army troops, government officials and media who encircled the two outposts that the armed men of the Jamaat al Muslimeen set up by force in the seat of Government power and at the sole television station operating in the country, the state-owned Trinidad and Tobago Television.

I was one of those people close to the periphery of this sudden siege on elected power, waiting for indicators of activity or a change in a confusing and mercurial status quo, but Raoul Pantin was on the inside.

A reporter and editor of some standing in Trindad's media, Pantin was at work in TTT, editing a report on Parliament when the Muslimeen arrived at TTT's doorstep, bristling with guns and confident in their capacity to change the country's leadership with small arms and faith.

Pantin's book about his experience, Days of Wrath, is paced like a thriller, albeit one that we've already read ahead to the end.

Pantin's book about his experience, Days of Wrath, is paced like a thriller, albeit one that we've already read ahead to the end.

On August 01, 1990, the 24 hostages were released at TTT, followed by young Muslimeen men who preceded their leader into rain slicked Maraval road, their guns held over their heads before they piled them on the wet asphalt under the watchful eyes of black clad, hooded army men.

The six days leading up to that grey evening in the rain had been life changing. From having a gun pointed at my head by a wild-eyed young man who had just picked up a rifle from a car outside the paper's rear entrance to ducking behind desks as the abductors in the Red House periodically opened fire on the Guardian's north face, the experience was a forced introduction to what it means to live under the gun in a lawless state.

For years, I've wondered what it was like inside the walls of the Red House and TTT for the people who had guns pointed at them continuously, their only contact with the outside world filtered by their captors and for the politicians, the terrible sound of weapons they once governed now directed against them.

Pantin's book answers some of those questions.

The sweep of his narrative seeks to embrace much of what happened during the six days that Abu Bakr and his followers brought Trinidad and Tobago to a halt.

The 1990 insurrection is much like the proverbial elephant described by blind men. There were so many aspects to the event that have never been publicly discussed or narrated by those who experienced them that it's possible no one has a truly comprehensive overview of the coup attempt.

After almost two decades, all that is publicly available about the Muslimeen insurrection are a few facets on a complicated and still disturbing event, little windows into what happened over those puzzling, terrifying days.

Days of Wrath is at its best when it recounts the events of July 27 through the eyes of its author. While it is sometimes necessary to break away from that relentless and necessarily narrow focus to give context and narrative detail to the arc of the story, the narrative weakens and falters when it attempts to feel for the rest of the elephant.

It’s possible to sense Pantin’s frustration at this, at having to fall back on anonymous sources and incomplete information, at the stonewalling of the Army, which, in his dry repetition of the response that must have met his every question, “does not discuss security matters.”

No one has ever written in any detail about what happened inside of the Red House, so Days of Wrath stands, almost 20 years after an Imam from Mucurapo road stormed TTT and commandeered the lone television station in the country to announce the “overthrow” of the elected government as the lone first hand account of the 1990 coup attempt.

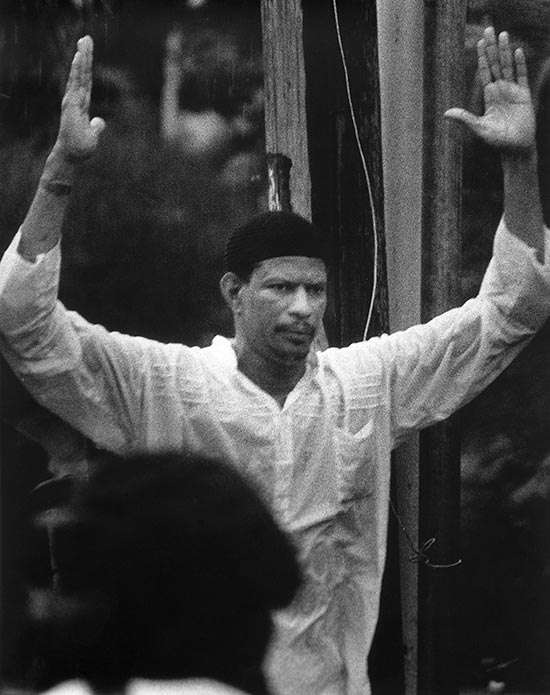

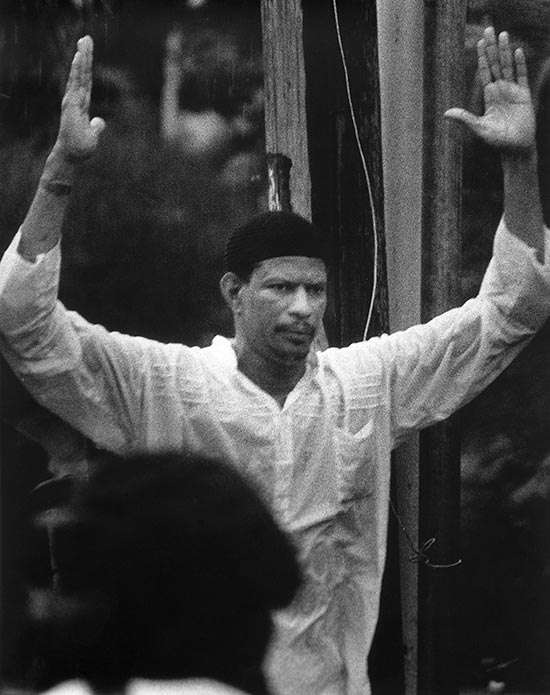

Pantin’s book traces in riveting detail how Abu Bakr’s coup dissolved from the broadcast high of the evening of the July 27 to the ignominious perp walk that the Muslimeen leader and his followers took from TTT along Maraval Road and into the rough hands of the Army’s special forces detail.

The author is polite, even deferential in his assessment of his fellow hostages, noting the occasional personal failing with almost apologetic detail. Surprisingly, he is also balanced in his assessment of his captors during that week of terror, recalling with intriguing, almost romantic detail the mood and tone of the hostage takers over their six days of shared captivity as the army laid siege outside the television station.

There are some irritating typographic errors in the book, minimal blemishes that stand out in a work that deserved another keen look by skilled proofreader, but overall Raoul Pantin’s retelling of the TTT experience is an overdue reminder that there is far much about the insurrection of 1990 that remains troubling and essentially unknown.

No political administration since the demise of the NAR has found it necessary to uncork the unpleasant vapours of those six days with a formal commission of inquiry.

The middle-class vote which fuelled the ascendancy of Prime Minister Robinson’s NAR government deserted the party, essentially wiping it from existence as a viable political entity.

The echoes of Abu Bakr’s attempt to overthrow the government of Trinidad and Tobago in 1990 continue to ripple through the country. Like waves from a far distant subsea disturbance, they break on the beaches of the island state like muted memories.

After the ease with which the broadcast media could be muzzled was so ably demonstrated, long observed restrictions on broadcast licenses were dropped and Trinidad and Tobago’s media landscape exploded.

Politics, given lively voice by a multiplicity of only marginally restrained talk radio stations, is more enthusiastic than ever but the murder rate in Trinidad and Tobago continues to spiral.

It’s almost impossible not to make some connections between a climate of lawlessness and weekly killings and the dark six days that Days of Wrath revisits, when young men first demonstrated how easy it was to use a gun to get what you want.

The 1990 Coup on Trinidad and Tobago

Raoul A Pantin

Photography and review by Mark Lyndersay, published in the May 2008 issue of the Caribbean Review of Books.

There’s a popular argument that the coup attempt in Trinidad and Tobago changed this twin-island nation forever, that the growth of violent crime over the last decade can be traced back to that act of pointless lawlessness and the distribution of guns on the evening of July 27, 1990.

But the actions of Imam Abu Bakr and his followers actually impacted directly on a relatively small sliver of the nation's population.

It's possible that no more than two thousand people were directly engaged in the events of the six days of fear and uncertainty that the insurrectionist Muslimeen brought to the Red House and TTT in the name of Islam and with the stated purpose of overthrowing the lawful government of Trinidad and Tobago.

Among that number I count the looters who pillaged Port of Spain, the police officers, army troops, government officials and media who encircled the two outposts that the armed men of the Jamaat al Muslimeen set up by force in the seat of Government power and at the sole television station operating in the country, the state-owned Trinidad and Tobago Television.

I was one of those people close to the periphery of this sudden siege on elected power, waiting for indicators of activity or a change in a confusing and mercurial status quo, but Raoul Pantin was on the inside.

A reporter and editor of some standing in Trindad's media, Pantin was at work in TTT, editing a report on Parliament when the Muslimeen arrived at TTT's doorstep, bristling with guns and confident in their capacity to change the country's leadership with small arms and faith.

On August 01, 1990, the 24 hostages were released at TTT, followed by young Muslimeen men who preceded their leader into rain slicked Maraval road, their guns held over their heads before they piled them on the wet asphalt under the watchful eyes of black clad, hooded army men.

The six days leading up to that grey evening in the rain had been life changing. From having a gun pointed at my head by a wild-eyed young man who had just picked up a rifle from a car outside the paper's rear entrance to ducking behind desks as the abductors in the Red House periodically opened fire on the Guardian's north face, the experience was a forced introduction to what it means to live under the gun in a lawless state.

For years, I've wondered what it was like inside the walls of the Red House and TTT for the people who had guns pointed at them continuously, their only contact with the outside world filtered by their captors and for the politicians, the terrible sound of weapons they once governed now directed against them.

Pantin's book answers some of those questions.

The sweep of his narrative seeks to embrace much of what happened during the six days that Abu Bakr and his followers brought Trinidad and Tobago to a halt.

The 1990 insurrection is much like the proverbial elephant described by blind men. There were so many aspects to the event that have never been publicly discussed or narrated by those who experienced them that it's possible no one has a truly comprehensive overview of the coup attempt.

After almost two decades, all that is publicly available about the Muslimeen insurrection are a few facets on a complicated and still disturbing event, little windows into what happened over those puzzling, terrifying days.

Days of Wrath is at its best when it recounts the events of July 27 through the eyes of its author. While it is sometimes necessary to break away from that relentless and necessarily narrow focus to give context and narrative detail to the arc of the story, the narrative weakens and falters when it attempts to feel for the rest of the elephant.

It’s possible to sense Pantin’s frustration at this, at having to fall back on anonymous sources and incomplete information, at the stonewalling of the Army, which, in his dry repetition of the response that must have met his every question, “does not discuss security matters.”

No one has ever written in any detail about what happened inside of the Red House, so Days of Wrath stands, almost 20 years after an Imam from Mucurapo road stormed TTT and commandeered the lone television station in the country to announce the “overthrow” of the elected government as the lone first hand account of the 1990 coup attempt.

Pantin’s book traces in riveting detail how Abu Bakr’s coup dissolved from the broadcast high of the evening of the July 27 to the ignominious perp walk that the Muslimeen leader and his followers took from TTT along Maraval Road and into the rough hands of the Army’s special forces detail.

The author is polite, even deferential in his assessment of his fellow hostages, noting the occasional personal failing with almost apologetic detail. Surprisingly, he is also balanced in his assessment of his captors during that week of terror, recalling with intriguing, almost romantic detail the mood and tone of the hostage takers over their six days of shared captivity as the army laid siege outside the television station.

There are some irritating typographic errors in the book, minimal blemishes that stand out in a work that deserved another keen look by skilled proofreader, but overall Raoul Pantin’s retelling of the TTT experience is an overdue reminder that there is far much about the insurrection of 1990 that remains troubling and essentially unknown.

No political administration since the demise of the NAR has found it necessary to uncork the unpleasant vapours of those six days with a formal commission of inquiry.

The middle-class vote which fuelled the ascendancy of Prime Minister Robinson’s NAR government deserted the party, essentially wiping it from existence as a viable political entity.

The echoes of Abu Bakr’s attempt to overthrow the government of Trinidad and Tobago in 1990 continue to ripple through the country. Like waves from a far distant subsea disturbance, they break on the beaches of the island state like muted memories.

After the ease with which the broadcast media could be muzzled was so ably demonstrated, long observed restrictions on broadcast licenses were dropped and Trinidad and Tobago’s media landscape exploded.

Politics, given lively voice by a multiplicity of only marginally restrained talk radio stations, is more enthusiastic than ever but the murder rate in Trinidad and Tobago continues to spiral.

It’s almost impossible not to make some connections between a climate of lawlessness and weekly killings and the dark six days that Days of Wrath revisits, when young men first demonstrated how easy it was to use a gun to get what you want.

blog comments powered by Disqus