BitDepth 818 - January 24

23/01/12 22:11 Filed in: BitDepth - January 2012

Noel Norton, local photographic giant, has passed away. This is a final note on his life. Read other stories about him here.

The winter of his heartbreak

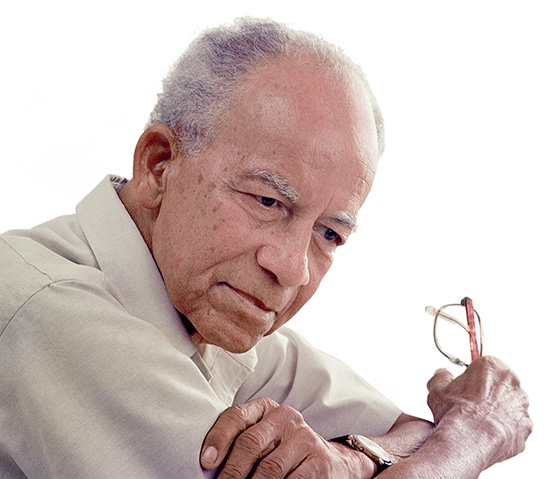

Noel Norton, photographed in 1999 by Mark Lyndersay.

Noel Norton is dead.

There, it’s said. Now I can contemplate the hard, uncompromising edges of those four words and their finality.

I met Noel Norton when he was roughly the same age that I am now. He was a mature, successful photographer with children almost my age, a thriving business on Marli Street, just a few buildings away from the American embassy, and a display wall in that space with continuous photographic inspiration.

It is one of the curiosities of our relationship, forged over processed film and dozens of dusty days in the Savannah on a Carnival Tuesday, that he never told me a single thing about the craft of photography, yet he taught me everything I know about being a photographer in Trinidad and Tobago.

The business model I work with today was inspired by a single comment he shared with me 25 years ago while I was staring at a particularly gorgeous photo of a young model at the beach, her hair and loose wrap flowing behind her.

I’d be lying if I said I understood it then, but I never forgot it, and six years ago when I returned to photography as a full time career after eight years spent in newspaper management and then corporate communications, I finally understood what he was telling me.

“The girls are lovely,” he said, “but it’s their mothers that spend the money.”

And those mothers kept coming, to be photographed, to have their families recorded as they grew up, got married and had children of their own. Norton Studios was built on his portraits of Trinidadian families who just wanted to be ennobled by his camera his lush lighting and his skin softening tricks.

Over the last six years and right up until two weeks ago, Noel continued to teach me what this business was about, what it took from you and what you were honour bound to give in return.

His work, shelf after shelf of it in a room at his home, is an unprecedented and continuous photographic record of Trinidad and Tobago’s development since the 1950’s and is unequalled anywhere in this country.

He worked at it until he couldn’t anymore and if there was one thing that Noel managed to fail at during the three and a half decades I knew him, it was retirement.

The Nortons shrank and finally closed the studio at Westmall, moving operations to their Diego Martin home. As the years went by, digital technology and family decisions led to them scaling back to a cosy apartment in the space, but the work continued with impressive industry.

The final meditation of his life, then, was an instruction on facing the inevitable end of a career. If the man was sometimes irritable, it was because the photographer became frustrated with the almost constant changes in technology that upset his routine.

He had flourished in a business in which you learned the principles of something and worked at mastering it for years. The digital era, with its quick, programmed solutions and demanding, almost constant learning curve came at a bad time for him.

Time is relentless. Noel began to have difficulties with his eyesight. Mary, the scaffolding of his soaring career, became grievously ill. The complications of digital colour correction and printing became increasingly confusing.

Carnival, some distance now from the agreeable festival he had begun photographing half-a-century before, was difficult, the costumes indistinguishable, the music unintelligible.

In 2010, I found myself presiding over the end of that era. That February I drove in through the gates to Dimanche Gras with Noel, the sun still low in the sky.

We found chairs, ate an early dinner and made ready for the hours of Dimanche Gras ahead. What happened over the next few hours will always haunt me, I think. Let’s just say that I made a lousy Mary Norton and by the end of the show, Noel’s camera was irreparably broken.

I’ll never forget walking back to the car that night, skipping over suspicious pools of water trailing away from sewage trucks, trying to make chit chat with Norts and knowing in my heart that he wouldn’t ever be back.

It wouldn’t be his last heartbreak. Never bitter, his work became progressively more challenging. His health was faltering. Mary, ailing for so long, finally passed away.

I worried about him then. Months before, he’d asked me to take him to a Chinese restaurant to buy lunch. After waiting for a while, I decided to go in. I found Noel staring at the illuminated menu board. Mary had always ordered lunch, and he had no idea what it was. We finally figured it out after describing it to an attendant, but Mary ran deep in his life in so many other ways.

At her funeral last August he looked so frail, so lost. The photographer stripped of his life partner and so much of his craft.

Still, he offered lessons in dignity, even in infirmity. Just a few days ago, he cracked wise with his nurse about his lunch.

This was still Sgt Norton, the bombardier who climbed into a massive British Lancaster to do battle lying on his chest, studying the terrain from its nose windows.

He was a teenager when he stared down death by flak shrapnel, and he hadn’t lost his grit in the 70 years since.

Related links...

BitDepth 799: The wind cries Mary

Noel and me (1999)

Understanding Noel (2005)

Sergeant NP Norton of the RAF

Noel Norton, photographed in 1999 by Mark Lyndersay.

Noel Norton is dead.

There, it’s said. Now I can contemplate the hard, uncompromising edges of those four words and their finality.

I met Noel Norton when he was roughly the same age that I am now. He was a mature, successful photographer with children almost my age, a thriving business on Marli Street, just a few buildings away from the American embassy, and a display wall in that space with continuous photographic inspiration.

It is one of the curiosities of our relationship, forged over processed film and dozens of dusty days in the Savannah on a Carnival Tuesday, that he never told me a single thing about the craft of photography, yet he taught me everything I know about being a photographer in Trinidad and Tobago.

The business model I work with today was inspired by a single comment he shared with me 25 years ago while I was staring at a particularly gorgeous photo of a young model at the beach, her hair and loose wrap flowing behind her.

I’d be lying if I said I understood it then, but I never forgot it, and six years ago when I returned to photography as a full time career after eight years spent in newspaper management and then corporate communications, I finally understood what he was telling me.

“The girls are lovely,” he said, “but it’s their mothers that spend the money.”

And those mothers kept coming, to be photographed, to have their families recorded as they grew up, got married and had children of their own. Norton Studios was built on his portraits of Trinidadian families who just wanted to be ennobled by his camera his lush lighting and his skin softening tricks.

Over the last six years and right up until two weeks ago, Noel continued to teach me what this business was about, what it took from you and what you were honour bound to give in return.

His work, shelf after shelf of it in a room at his home, is an unprecedented and continuous photographic record of Trinidad and Tobago’s development since the 1950’s and is unequalled anywhere in this country.

He worked at it until he couldn’t anymore and if there was one thing that Noel managed to fail at during the three and a half decades I knew him, it was retirement.

The Nortons shrank and finally closed the studio at Westmall, moving operations to their Diego Martin home. As the years went by, digital technology and family decisions led to them scaling back to a cosy apartment in the space, but the work continued with impressive industry.

The final meditation of his life, then, was an instruction on facing the inevitable end of a career. If the man was sometimes irritable, it was because the photographer became frustrated with the almost constant changes in technology that upset his routine.

He had flourished in a business in which you learned the principles of something and worked at mastering it for years. The digital era, with its quick, programmed solutions and demanding, almost constant learning curve came at a bad time for him.

Time is relentless. Noel began to have difficulties with his eyesight. Mary, the scaffolding of his soaring career, became grievously ill. The complications of digital colour correction and printing became increasingly confusing.

Carnival, some distance now from the agreeable festival he had begun photographing half-a-century before, was difficult, the costumes indistinguishable, the music unintelligible.

In 2010, I found myself presiding over the end of that era. That February I drove in through the gates to Dimanche Gras with Noel, the sun still low in the sky.

We found chairs, ate an early dinner and made ready for the hours of Dimanche Gras ahead. What happened over the next few hours will always haunt me, I think. Let’s just say that I made a lousy Mary Norton and by the end of the show, Noel’s camera was irreparably broken.

I’ll never forget walking back to the car that night, skipping over suspicious pools of water trailing away from sewage trucks, trying to make chit chat with Norts and knowing in my heart that he wouldn’t ever be back.

It wouldn’t be his last heartbreak. Never bitter, his work became progressively more challenging. His health was faltering. Mary, ailing for so long, finally passed away.

I worried about him then. Months before, he’d asked me to take him to a Chinese restaurant to buy lunch. After waiting for a while, I decided to go in. I found Noel staring at the illuminated menu board. Mary had always ordered lunch, and he had no idea what it was. We finally figured it out after describing it to an attendant, but Mary ran deep in his life in so many other ways.

At her funeral last August he looked so frail, so lost. The photographer stripped of his life partner and so much of his craft.

Still, he offered lessons in dignity, even in infirmity. Just a few days ago, he cracked wise with his nurse about his lunch.

This was still Sgt Norton, the bombardier who climbed into a massive British Lancaster to do battle lying on his chest, studying the terrain from its nose windows.

He was a teenager when he stared down death by flak shrapnel, and he hadn’t lost his grit in the 70 years since.

Related links...

BitDepth 799: The wind cries Mary

Noel and me (1999)

Understanding Noel (2005)

Sergeant NP Norton of the RAF

blog comments powered by Disqus