BitDepth#827 - March 27

26/03/12 21:27 Filed in: BitDepth - March 2012

My school principal, Courtney Nicholls, a remarkable, witty leader of young boys who would one day become men, passed away in late March. This is a remembrance of his presence in my teenage life.

To sir with love

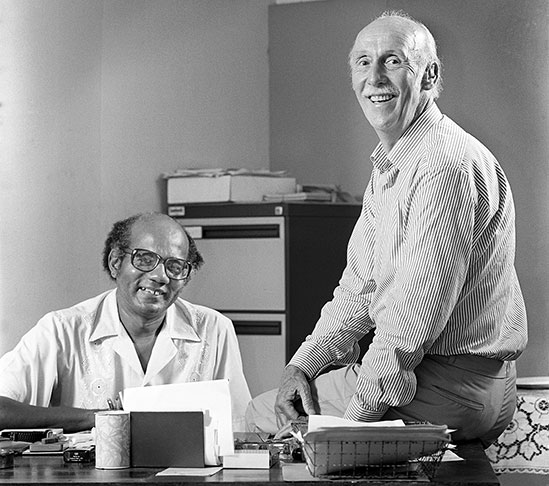

For Trinity College’s 25th anniversary, I photographed Courtney Nicholls and Peter Helps, the school’s first two principals, at Nicholls’ office. Photo by Mark Lyndersay.

On the surface of it, Courtney Nicholls really didn’t look anything like Werner Klemperer, the actor who played Colonel Wilhelm Klink on the WWII prison comedy Hogan’s Heroes.

There was some likeness in the hairstyle; a severely receding hairline that left a hedge of hair arcing from temple to temple and glasses, though Klink affected a monocle and Nicholls always wore thick glasses with heavy rims.

Unlike the daft Germans running that camp though, Courtney Nicholls saw everything that went on at Trinity College in the years I attended from 1969 to 1976.

Teachers are always part of the conversation when classmates get together and while time and maturity bring fresh perspectives and often admiration for one’s teachers, but the one who was consistently held in reverence was Courtney Nicholls.

Why did his nickname, Klink, last for so long? Perhaps it was being essentially imprisoned in a remote green wilderness (no Moka Raton and golf course then, just orange trees with sour fruit) with a man who matched rigorous discipline with a subtle but devastating sense of humour.

Nicholls never treated students like children or fools. He never hesitated to discipline or to raise his hand for a particularly devastating clout, but he respected the capacity of his charges to self-govern and make sensible decisions after being offered a few words of wisdom.

Every memorable story about Nicholls throws both aspects of his personality into relief. His robust support of the school football team was as important as his withering glare and frown of disappointment when you got caught out.

Here’s one story out of many. Nicholls quickly deduced that we were using the sixth form toilet as a smoking room (we’d discover later that wafts of cigarette smoke would appear in the teacher’s loo above) and let us know by standing in a hallway as we walked by after a grand puff out and making a public show of sniffing in the air, muttering with a stage whisper, “Hmm. Witco.”

A few days later, the groundsman, Reds, knocked on the door to our damp little smoking room and brought us an ashtray. We’d been tossing the butts through the brickwork into a particularly difficult area to clean, apparently.

As a disciplinarian he was notoriously inventive. After two perversely misbehaved classmates made a mockery of the school’s punishment system, the once-feared recorded imposition, by racking up hundreds of them and resisted caning, he set them to transcribing books. Those who couldn’t hear and apparently couldn’t feel, would read and write.

I only had a few history classes with him in first form, and my most influential teachers would always be the iconoclastic Archie Edwards and Shirley McAlpin, Charlene Ogle and Hugh Spicer, who guided me through the miracle of words.

But Nicholls was an involved principal and every student felt his presence.

The firm, sometimes fierce man would become a gentle, almost painfully shy person later in life, particularly when he met his former students, it seemed.

The school had an indefinable, but potent impact on me and everytime I’ve started a course of study since then, I’ve been disappointed by the experience and more compellingly, the teachers.

I haven’t been back to school anywhere since I left Trinity for the last time in school uniform in 1977, yet there hasn’t been a day since then that I haven’t been busy studying something or other.

I’ve also found it difficult to embrace the school with the gusto that a happy alumnus should. I loved Trinity College, and my experience there, under the leadership of Courtney Nicholls, was one of the richest and most profoundly formative times of my life, but my Trinity is gone.

It’s one of the problems the young school is still to come to grips with. Photographing the first two principals two decades ago, I was struck by the indifference that the “Phelps” men had for Nicholls. He wasn’t their principal. He wasn’t their Trinity.

It’s a phenomenon that I’ve discussed with the alumni association. Thirty-six years on, there’s little of the school I experienced that’s still there. Even the physical structure, improved greatly since the 70’s, is different. It isn’t the school of my memory anymore either. I’m a Klink man, and the experiences of later students under their principals sound alien to me.

If Peter Helps was the founding principal, Nicholls was its formative leader, blending discipline with a wit that echoes down through the years through his students.

With the passing of Courtney Nicholls, Klink is dead.

That’s a full-stop to my era that’s impossible to ignore.

For Trinity College’s 25th anniversary, I photographed Courtney Nicholls and Peter Helps, the school’s first two principals, at Nicholls’ office. Photo by Mark Lyndersay.

On the surface of it, Courtney Nicholls really didn’t look anything like Werner Klemperer, the actor who played Colonel Wilhelm Klink on the WWII prison comedy Hogan’s Heroes.

There was some likeness in the hairstyle; a severely receding hairline that left a hedge of hair arcing from temple to temple and glasses, though Klink affected a monocle and Nicholls always wore thick glasses with heavy rims.

Unlike the daft Germans running that camp though, Courtney Nicholls saw everything that went on at Trinity College in the years I attended from 1969 to 1976.

Teachers are always part of the conversation when classmates get together and while time and maturity bring fresh perspectives and often admiration for one’s teachers, but the one who was consistently held in reverence was Courtney Nicholls.

Why did his nickname, Klink, last for so long? Perhaps it was being essentially imprisoned in a remote green wilderness (no Moka Raton and golf course then, just orange trees with sour fruit) with a man who matched rigorous discipline with a subtle but devastating sense of humour.

Nicholls never treated students like children or fools. He never hesitated to discipline or to raise his hand for a particularly devastating clout, but he respected the capacity of his charges to self-govern and make sensible decisions after being offered a few words of wisdom.

Every memorable story about Nicholls throws both aspects of his personality into relief. His robust support of the school football team was as important as his withering glare and frown of disappointment when you got caught out.

Here’s one story out of many. Nicholls quickly deduced that we were using the sixth form toilet as a smoking room (we’d discover later that wafts of cigarette smoke would appear in the teacher’s loo above) and let us know by standing in a hallway as we walked by after a grand puff out and making a public show of sniffing in the air, muttering with a stage whisper, “Hmm. Witco.”

A few days later, the groundsman, Reds, knocked on the door to our damp little smoking room and brought us an ashtray. We’d been tossing the butts through the brickwork into a particularly difficult area to clean, apparently.

As a disciplinarian he was notoriously inventive. After two perversely misbehaved classmates made a mockery of the school’s punishment system, the once-feared recorded imposition, by racking up hundreds of them and resisted caning, he set them to transcribing books. Those who couldn’t hear and apparently couldn’t feel, would read and write.

I only had a few history classes with him in first form, and my most influential teachers would always be the iconoclastic Archie Edwards and Shirley McAlpin, Charlene Ogle and Hugh Spicer, who guided me through the miracle of words.

But Nicholls was an involved principal and every student felt his presence.

The firm, sometimes fierce man would become a gentle, almost painfully shy person later in life, particularly when he met his former students, it seemed.

The school had an indefinable, but potent impact on me and everytime I’ve started a course of study since then, I’ve been disappointed by the experience and more compellingly, the teachers.

I haven’t been back to school anywhere since I left Trinity for the last time in school uniform in 1977, yet there hasn’t been a day since then that I haven’t been busy studying something or other.

I’ve also found it difficult to embrace the school with the gusto that a happy alumnus should. I loved Trinity College, and my experience there, under the leadership of Courtney Nicholls, was one of the richest and most profoundly formative times of my life, but my Trinity is gone.

It’s one of the problems the young school is still to come to grips with. Photographing the first two principals two decades ago, I was struck by the indifference that the “Phelps” men had for Nicholls. He wasn’t their principal. He wasn’t their Trinity.

It’s a phenomenon that I’ve discussed with the alumni association. Thirty-six years on, there’s little of the school I experienced that’s still there. Even the physical structure, improved greatly since the 70’s, is different. It isn’t the school of my memory anymore either. I’m a Klink man, and the experiences of later students under their principals sound alien to me.

If Peter Helps was the founding principal, Nicholls was its formative leader, blending discipline with a wit that echoes down through the years through his students.

With the passing of Courtney Nicholls, Klink is dead.

That’s a full-stop to my era that’s impossible to ignore.

blog comments powered by Disqus