BitDepth#864 - December 11

11/12/12 17:45 Filed in: BitDepth - December 2012

The author of one of my favorite apps passed away in June. What does this mean for his software? What happens to software when their creators go away?

When software goes away

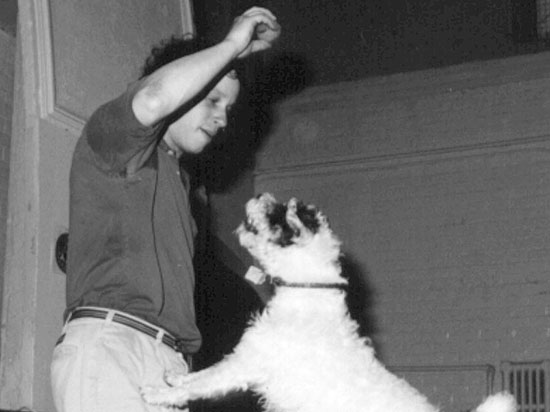

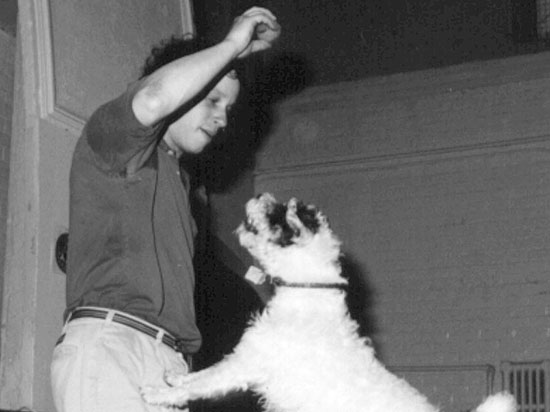

Evan Gross and Thunder, a flyball champion terrier. Photograph courtesy Stephanie Gross.

In early September, Google bought software developer Nik Software and Nik's online community of users went insane. Nik’s products, for those of you who do not live in Adobe Photoshop, are a line of plug-ins for the image editor that make sophisticated transformations and effects very accessible.

Google didn’t buy the company for that narrow market of users. They were interested in Snapseed, an iOS app that wrapped some of Nik’s plug-in magic into a simple app aimed at cameraphone enthusiasts.

There seemed to be little confidence that the search behemoth would have the same love for Nik’s Photoshop plug-ins, which I’d been smitten with earlier this year.

The outcry was loud enough and sustained enough that Vic Gundotra, Senior VP for Engineering posted words of reassurance to his blog: “I also want to make something clear: we're going to continue offering and improving Nik's high-end tools and plug-ins.”

“Professionals across the globe use Nik to create the perfect moment in their photographs, and we care deeply about their artistry.”

It’s not as if a large company buying successful software has always or even often worked out well for its customers. Macromedia’s Freehand disappeared, to the anguish of its many fans, after Adobe bought it and killed the product in favour of Illustrator.

Aldus Persuasion, an early leader in the presentation market, also disappeared in Adobe’s care. Picasa, a low end image editor and organiser acquired by Google in 2004 has largely languished under Google’s stewardship.

I own software from large established companies because they work well and are best in class products. Microsoft’s Office. Apple’s Pages and iTunes. Adobe’s Photoshop and Lightroom and Intuit’s Quicken are products that I rely on, but there are more than two-dozen other, smaller products that I use with equal regularity that come from tiny companies or individuals who have crafted focused, single purpose tools that outperform general purpose counterparts or provide extended and quite specific features.

Most of these are shareware, applications offered on trial online and licensed for small fees.

Among them is SpellCatcher, which I’ve written about here.

A month ago, I ran into some licensing problems with SpellCatcher and tried to contact the author about it.

That’s when I got some terrible news. Evan Gross, the author had passed away in June after suffering a brain haemorrhage at the age of 51.

I was stunned. I never knew Gross, sharing a brief e-mail or two with him over the years when issues arose, but over all that time he was the capable but faceless author of Thunder 7, the product I’d begun using in 1995 and it’s successor, SpellCatcher, which I’d been using ever since.

For a year or so, the Guardian bought a small site license for the product to create a unified spelling database for the subeditors, but that didn’t last.

By the time of his passing, Gross had updated his software from System 6 to Mac OS 10.7, spanning three MacOS eras and three processor (and coding platform) changes while improving the product’s exemplary focus on text management. Very few Macintosh shareware products can boast that pedigree.

It’s possible to duplicate much of what SpellCatcher offers with a mix of the Mac’s built-in dictionary and GREP search and replace routines, but I’ve never found anything that matched its writer-focused elegance and simplicity.

Gross’ sister Stephanie, who shared the sad news with me, worked with him on the project in design and promotion but isn’t a programmer. Some users are experiencing issues with the software on the newest version of the MacOS, and she is logging those issues while searching for someone to take over the product’s development.

It’s a strange, slightly weird situation for a user. I’ve had a relationship with the late Evan Gross for just slightly under 20 years. We’ve never met, but I’ve bought every update of his product and have relied on it for most of that time on an almost daily basis.

Selfishly, I wonder who will take up the challenge of keeping this software going. The loss is hardly financial. SpellCatcher sells for less than the sales tax on most professional software.

The lack of any serious competition in the space speaks to both the intricacy of the work that Gross put into it, mostly manifest in its seductive simplicity, and the small profile of users likely to find it useful.

It’s possible that SpellCatcher will simply go away, its user base collapsing as new OS upgrades appear that demand the software tricks that many shareware authors used to work around limitations in Apple’s official programming interface.

Until then, Evan Gross won’t be truly gone as long as I can activate his life’s work from my dock and put it to work. Excuse me while I do that now.

Evan Gross and Thunder, a flyball champion terrier. Photograph courtesy Stephanie Gross.

In early September, Google bought software developer Nik Software and Nik's online community of users went insane. Nik’s products, for those of you who do not live in Adobe Photoshop, are a line of plug-ins for the image editor that make sophisticated transformations and effects very accessible.

Google didn’t buy the company for that narrow market of users. They were interested in Snapseed, an iOS app that wrapped some of Nik’s plug-in magic into a simple app aimed at cameraphone enthusiasts.

There seemed to be little confidence that the search behemoth would have the same love for Nik’s Photoshop plug-ins, which I’d been smitten with earlier this year.

The outcry was loud enough and sustained enough that Vic Gundotra, Senior VP for Engineering posted words of reassurance to his blog: “I also want to make something clear: we're going to continue offering and improving Nik's high-end tools and plug-ins.”

“Professionals across the globe use Nik to create the perfect moment in their photographs, and we care deeply about their artistry.”

It’s not as if a large company buying successful software has always or even often worked out well for its customers. Macromedia’s Freehand disappeared, to the anguish of its many fans, after Adobe bought it and killed the product in favour of Illustrator.

Aldus Persuasion, an early leader in the presentation market, also disappeared in Adobe’s care. Picasa, a low end image editor and organiser acquired by Google in 2004 has largely languished under Google’s stewardship.

I own software from large established companies because they work well and are best in class products. Microsoft’s Office. Apple’s Pages and iTunes. Adobe’s Photoshop and Lightroom and Intuit’s Quicken are products that I rely on, but there are more than two-dozen other, smaller products that I use with equal regularity that come from tiny companies or individuals who have crafted focused, single purpose tools that outperform general purpose counterparts or provide extended and quite specific features.

Most of these are shareware, applications offered on trial online and licensed for small fees.

Among them is SpellCatcher, which I’ve written about here.

A month ago, I ran into some licensing problems with SpellCatcher and tried to contact the author about it.

That’s when I got some terrible news. Evan Gross, the author had passed away in June after suffering a brain haemorrhage at the age of 51.

I was stunned. I never knew Gross, sharing a brief e-mail or two with him over the years when issues arose, but over all that time he was the capable but faceless author of Thunder 7, the product I’d begun using in 1995 and it’s successor, SpellCatcher, which I’d been using ever since.

For a year or so, the Guardian bought a small site license for the product to create a unified spelling database for the subeditors, but that didn’t last.

By the time of his passing, Gross had updated his software from System 6 to Mac OS 10.7, spanning three MacOS eras and three processor (and coding platform) changes while improving the product’s exemplary focus on text management. Very few Macintosh shareware products can boast that pedigree.

It’s possible to duplicate much of what SpellCatcher offers with a mix of the Mac’s built-in dictionary and GREP search and replace routines, but I’ve never found anything that matched its writer-focused elegance and simplicity.

Gross’ sister Stephanie, who shared the sad news with me, worked with him on the project in design and promotion but isn’t a programmer. Some users are experiencing issues with the software on the newest version of the MacOS, and she is logging those issues while searching for someone to take over the product’s development.

It’s a strange, slightly weird situation for a user. I’ve had a relationship with the late Evan Gross for just slightly under 20 years. We’ve never met, but I’ve bought every update of his product and have relied on it for most of that time on an almost daily basis.

Selfishly, I wonder who will take up the challenge of keeping this software going. The loss is hardly financial. SpellCatcher sells for less than the sales tax on most professional software.

The lack of any serious competition in the space speaks to both the intricacy of the work that Gross put into it, mostly manifest in its seductive simplicity, and the small profile of users likely to find it useful.

It’s possible that SpellCatcher will simply go away, its user base collapsing as new OS upgrades appear that demand the software tricks that many shareware authors used to work around limitations in Apple’s official programming interface.

Until then, Evan Gross won’t be truly gone as long as I can activate his life’s work from my dock and put it to work. Excuse me while I do that now.

blog comments powered by Disqus