BitDepth#892 - July 02

01/07/13 19:27 Filed in: BitDepth - July 2013

DC Comics' flagship superhero Superman makes it to the screen in a major blockbuster film but loses some important elements of his character along the way.

Man of tin

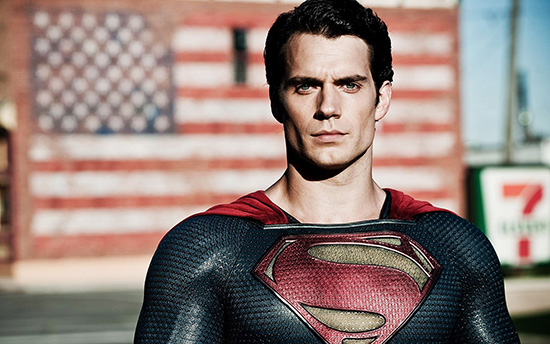

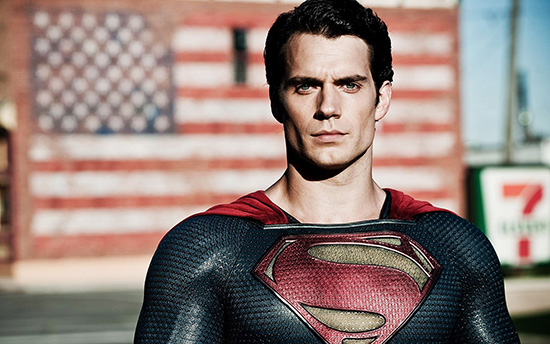

Henry Cavill portrays the Judeo-Christian saviour as all-American superhero in Man of Steel.

The search for a great movie about DC Comics’flagship hero Superman has been continuing for decades now. It’s been an astonishing 35 years since Richard Donner made his film with newcomer Christopher Reeve, as magical a piece of filmmaking as 1933’s King Kong was in its day, a narrative that married human nature, special effects and high concept fantasy into a story that anyone could empathise with.

It’s notable that in this version of the story, the Kryptonian refugee is rarely called Superman. It's as if the name, in 2013, 75 years after it first appeared on cheap newsprint, was somehow gauche, a matter to be glossed over with embarrassment.

When Lois Lane (Amy Adams) first proposes the name to the costumed alien, a scratchy microphone breaks in to smother the word, like an embarrassed parent stunned to hear something naughty being said by an errant child.

That attitude, a vaguely embarrassed enthusiasm to play with Superman’s toys while adamantly describing them as art is threaded all the way through Zack Snyder’s Man of Steel.

It’s not that the film is bad, it’s just that it’s so reluctant to acknowledge its source material, to accept that the Clark Kent/Superman archetype is meant to inspire new realities, not trudge along in the sludge of old ones.

That’s the problem, really, with Man of Steel. The diligence spent on bringing insistent reality to a insanely powerful superhuman in a skin-tight suit ends up wholly misplaced here, the stony seriousness of the proceedings clamping leaden weights on the fantasy that a man can fly.

Jor-El (Russel Crowe, again a bad-ass) explains that he sent his only begotten son to Earth so that he might experience choice, something long bred out of Kryptonians.

But Kal-El (a searingly attractive Henry Cavill) spends his entire life doing anything but choosing. He follows Pa Kent’s instructions with such fidelity that he allows him to die rather than defy him.

When he discovers a digital shade of his Kryptonian father, he follows those instructions to the letter as well.

Pretty much the only decision he makes on his own in the entire film is the wrong one, choosing to kill. It’s an choice that the Superman of the comics made just once, in similar circumstances, and lamented for uncounted issues thereafter, almost driven mad by the experience.

There’s no room for such recriminations in Snyder’s film and what’s left is an unrecognisable man in tights destroying everything in sight.

Efforts at mining the Christian allegory at the heart of the Superman mythos are just ham-handed. Clark Kent spends 33 years in varying wildernesses on earth. At one critical point in the film he strikes a Jesus Christ pose before rocketing into action.

If you want a real world Superman biblical allegory, explore the story of the two wide-eyed Jewish boys who were targeted by authority, sold out for a handful of cash and were left to suffer for decades before being rescued by compassionate believers.

That’s the story of Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster who created the iconic hero, crafting a character that’s become a part of global mythology and the foundation of the entire comics medium.

But there’s precious little of Siegel and Schuster’s naive and blustery hero here. Like the modern Star Trek, which offers little of Gene Roddenberry’s intent while mining his stories and characters, Man of Steel is a dark, paranoid reimagining of the brighter, more colourful character that sparked a revolution in comics just as they were about to disappear.

An audience might want to cheer the handsome Cavill, to marvel at the 21st century effects that allow the hero float so effortlessly through the film (after some amusing scenes in which he blunders about learns to fly), to cheer his efforts to save humanity, but the film ultimately takes a painful and bloody tinkle on any such inclinations.

This Kal-El is simply terrified of the world and its opinionated, emotionally erratic people. His time in Kansas seems to have made him a simpleton and his adventures in leaving that world are much the poorer for it.

A shockingly violent fight between Kal-El and Faora (Antje Traue) lays waste to much of Smallville, the small Kansas town where Clark Kent grew up, stunted and lamed by his father’s fears, but that’s soon eclipsed by the battle with Zod in Metropolis.

“He saved the city,” someone says after that epic fight, which put the illusion of concrete and steel to the fanciful drawings that have levelled countless metropoles in the world of comics. But the dusty wreckage of hollowed out buildings on the horizon would make anyone wonder what possible meaning of the word save might apply here.

It’s a pity that Clark Kent didn’t meet Colonel Nathan Hardy (Christopher Meloni, or as everyone calls him, Stabler) under better circumstances.

The character, a tough grunt who faces down the superhuman in blue and red and Faora with a wee little knife repeatedly offers the film’s one unequivocal portrayal of heroism in the face of danger.

The Superman that makes it to the screen tends to be reflect the ideals of America when it’s created.

In 1951 he was a barrel-chested father figure, George Reeves’ stoic good cheer more reassuring than the doubtful powers he rarely demonstrated.

Christopher Reeve’s 1978 Superman was charming, handsome and very much an everyman, his bumbling Clark Kent a tour de force counterpoint to his beefy, righteous costumed alter ego.

For 1993’s Lois and Clark, Dean Cain was mostly a self-absorbed, lovelorn human more engrossed in his romance with Lois Lane (Teri Hatcher) than in anything he did in a costume.

Tom Welling’s Clark Kent in Smallville (2001) was as crippled by teen angst as the frequent appearances of Kryptonite, but he surrounded himself with hip, beautiful people as a happy counter to the deadly rocks.

Brandon Routh in Superman Returns (2006) attempted to resurrect the charm of Reeve’s version of the hero but only created a mausoleum to past greatness.

Man of Steel offers us a Superman who seems to regret his vast power, is reluctant to use it and despite spending his entire life on Earth, doesn’t seem to have any idea how to relate to actual humans.

Disagree? Comments are welcome!

Henry Cavill portrays the Judeo-Christian saviour as all-American superhero in Man of Steel.

The search for a great movie about DC Comics’flagship hero Superman has been continuing for decades now. It’s been an astonishing 35 years since Richard Donner made his film with newcomer Christopher Reeve, as magical a piece of filmmaking as 1933’s King Kong was in its day, a narrative that married human nature, special effects and high concept fantasy into a story that anyone could empathise with.

It’s notable that in this version of the story, the Kryptonian refugee is rarely called Superman. It's as if the name, in 2013, 75 years after it first appeared on cheap newsprint, was somehow gauche, a matter to be glossed over with embarrassment.

When Lois Lane (Amy Adams) first proposes the name to the costumed alien, a scratchy microphone breaks in to smother the word, like an embarrassed parent stunned to hear something naughty being said by an errant child.

That attitude, a vaguely embarrassed enthusiasm to play with Superman’s toys while adamantly describing them as art is threaded all the way through Zack Snyder’s Man of Steel.

It’s not that the film is bad, it’s just that it’s so reluctant to acknowledge its source material, to accept that the Clark Kent/Superman archetype is meant to inspire new realities, not trudge along in the sludge of old ones.

That’s the problem, really, with Man of Steel. The diligence spent on bringing insistent reality to a insanely powerful superhuman in a skin-tight suit ends up wholly misplaced here, the stony seriousness of the proceedings clamping leaden weights on the fantasy that a man can fly.

Jor-El (Russel Crowe, again a bad-ass) explains that he sent his only begotten son to Earth so that he might experience choice, something long bred out of Kryptonians.

But Kal-El (a searingly attractive Henry Cavill) spends his entire life doing anything but choosing. He follows Pa Kent’s instructions with such fidelity that he allows him to die rather than defy him.

When he discovers a digital shade of his Kryptonian father, he follows those instructions to the letter as well.

Pretty much the only decision he makes on his own in the entire film is the wrong one, choosing to kill. It’s an choice that the Superman of the comics made just once, in similar circumstances, and lamented for uncounted issues thereafter, almost driven mad by the experience.

There’s no room for such recriminations in Snyder’s film and what’s left is an unrecognisable man in tights destroying everything in sight.

Efforts at mining the Christian allegory at the heart of the Superman mythos are just ham-handed. Clark Kent spends 33 years in varying wildernesses on earth. At one critical point in the film he strikes a Jesus Christ pose before rocketing into action.

If you want a real world Superman biblical allegory, explore the story of the two wide-eyed Jewish boys who were targeted by authority, sold out for a handful of cash and were left to suffer for decades before being rescued by compassionate believers.

That’s the story of Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster who created the iconic hero, crafting a character that’s become a part of global mythology and the foundation of the entire comics medium.

But there’s precious little of Siegel and Schuster’s naive and blustery hero here. Like the modern Star Trek, which offers little of Gene Roddenberry’s intent while mining his stories and characters, Man of Steel is a dark, paranoid reimagining of the brighter, more colourful character that sparked a revolution in comics just as they were about to disappear.

An audience might want to cheer the handsome Cavill, to marvel at the 21st century effects that allow the hero float so effortlessly through the film (after some amusing scenes in which he blunders about learns to fly), to cheer his efforts to save humanity, but the film ultimately takes a painful and bloody tinkle on any such inclinations.

This Kal-El is simply terrified of the world and its opinionated, emotionally erratic people. His time in Kansas seems to have made him a simpleton and his adventures in leaving that world are much the poorer for it.

A shockingly violent fight between Kal-El and Faora (Antje Traue) lays waste to much of Smallville, the small Kansas town where Clark Kent grew up, stunted and lamed by his father’s fears, but that’s soon eclipsed by the battle with Zod in Metropolis.

“He saved the city,” someone says after that epic fight, which put the illusion of concrete and steel to the fanciful drawings that have levelled countless metropoles in the world of comics. But the dusty wreckage of hollowed out buildings on the horizon would make anyone wonder what possible meaning of the word save might apply here.

It’s a pity that Clark Kent didn’t meet Colonel Nathan Hardy (Christopher Meloni, or as everyone calls him, Stabler) under better circumstances.

The character, a tough grunt who faces down the superhuman in blue and red and Faora with a wee little knife repeatedly offers the film’s one unequivocal portrayal of heroism in the face of danger.

The Superman that makes it to the screen tends to be reflect the ideals of America when it’s created.

In 1951 he was a barrel-chested father figure, George Reeves’ stoic good cheer more reassuring than the doubtful powers he rarely demonstrated.

Christopher Reeve’s 1978 Superman was charming, handsome and very much an everyman, his bumbling Clark Kent a tour de force counterpoint to his beefy, righteous costumed alter ego.

For 1993’s Lois and Clark, Dean Cain was mostly a self-absorbed, lovelorn human more engrossed in his romance with Lois Lane (Teri Hatcher) than in anything he did in a costume.

Tom Welling’s Clark Kent in Smallville (2001) was as crippled by teen angst as the frequent appearances of Kryptonite, but he surrounded himself with hip, beautiful people as a happy counter to the deadly rocks.

Brandon Routh in Superman Returns (2006) attempted to resurrect the charm of Reeve’s version of the hero but only created a mausoleum to past greatness.

Man of Steel offers us a Superman who seems to regret his vast power, is reluctant to use it and despite spending his entire life on Earth, doesn’t seem to have any idea how to relate to actual humans.

Disagree? Comments are welcome!

blog comments powered by Disqus