On Marlon James

06/01/14 22:00 Filed in: Interview

In search of identity

Originally published in in the Sunday Guardian Arts Magazine for January 05, 2014

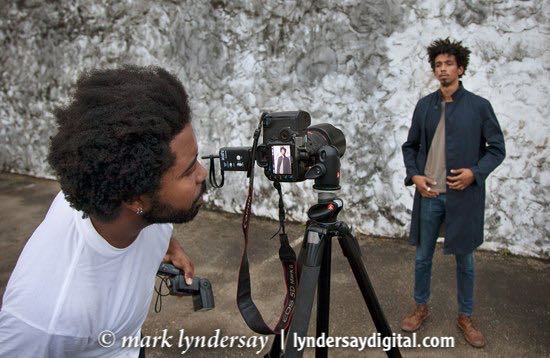

Marlon James reviews a capture of Alex Girvan during a shoot at a Duke Street car park on December 20. Photograph by Mark Lyndersay

“I’ve never felt like I belonged in the Caribbean,” says photographer Marlon James as we walk briskly up Henry Street in Port of Spain.

This is how the Jamaican photographer and artist has been experiencing much of Trinidad and Tobago since he moved here in January.

Strolling and striding his way through much of his measured and introspective interaction with a new landscape and people.

Much of his photography over the last ten years in Jamaica has been a search for his identity as a young man in the region.

On an overcast evening walking up a distinctly gray street under a brooding sky, Marlon James is again engaged in that exercise. We cut a quite ordinary profile as a group, distinguished only by our fast pace.

James is wearing jeans, and a white t-shirt and one hell of an equipment load in his worn backpack, his subject, architect Alex Girvan is all spiky dreads, jeans and a long gray coat that makes him look like more of a factory floor supervisor than a Matrix wannabe.

James is looking for a particular parking lot in the city that has old stone walls painted white, but we find the gate firmly locked. The rain is a menacing sprinkle now, and the light is disappearing.

A block further along on Duke Street we find another lot with a promising wall and a dour security guard. James ducks in quickly and flashes a charming smile and asks permission to use the spot for his photo.

He quickly sets up a tripod, wrestles with a slack ball-head and begins directing his subject through a series of poses inspired by his observation of Girvan’s gestures movements.

James’ style is disarmingly simple. He gets in close with a radio controlled handheld flash, gesturing and coaxing Girvan who has a flair for the moody pose while urging his subject to look into the lens and not at him.

“People tell me that my subjects tend to be a bit...well-to-do,” James notes after we part company with Girvan.

It isn’t surprising, given that James’ parents were bankers and he grew up in Jamaica as an “Uptown” boy, someone who had a full and paid education, whose family could fly out of the island regularly.

“I was really more middle-class,” he admits with a shrug.

Those professional parents proved to be supportive of their creative son, even more so when he began to get recognition for his work.

At 33, he’s comfortable admitting that his mother got him his gear when he made the shift from sculpture to photography, a change he acknowledges came because of the lure of the ‘instant gratification’of the medium.

When he made that decision, instant meant something else entirely in photography.

“I could process a roll of film and go into the darkroom to develop it,” James said.

“My sculpture would take weeks to take shape. I fell in love with the darkroom.”

He got serious with photography in 2003, but his first big break came in 2008 when he shot for Red Bull, then shortly after that for Red Stripe. James was also building a collection of portraits of people in the arts community in Jamaica when he began hearing that his prospects as an artist might significantly improve in T&T.

But it wasn’t until he started meeting people in the Trinidad arts community after moving here that he began to consider pursuing his portrait project locally.

He started a couple of projects soon after arriving, at least one sparked by the thriving night life in the city that he calls Night Shift, photographs of vendors working late at night.

Marlon James has been doing some commercial work while he works his way through these projects, shooting for advertising agencies and magazines.

“The work that I’ve been getting has been able to sustain me,” he said.

“In Jamaica, I’d have to have a nine to five job and probably some side jobs. Some of the work has been hard and fast, but some of it has offered creative freedom and I’ve appreciated that.”

In March 2014 he’ll find out whether moving to T&T was the right move for him as an artist with work to show and sell. Along with group shows in Holland and Washington, he plans a solo show in Trinidad.

“You can’t sell your work in Jamaica for what you’d get for it internationally,” he says.

“Except for a few collectors, the economy just won’t support those prices.”

Whether or not things work out financially, James has been greatly heartened by his experiences in Trinidad over his first year.

He admits to being lonely some of the time and hasn’t gathered the circle of friends and support he had in Jamaica, but appreciates the willingness of local artists to talk and collaborate.

James is particularly hopeful about the possibility of working with Melissa Matthews, a recently returned multimedia artist on a project.

Most striking for the photographer who does much of his work with subjects in their environment has been the way he has been received.

“People are more accepting of the presence of a photographer here, I’ve found.”

Marlon James is known as a portrait photographer, much of his previous work cleanly isolating his subjects from their backgrounds and focusing on still, patient engagements with the lens.

The theatre in his work plays out behind the expressions of his subjects, raising questions about the interplay between photographer and subject, emotional context and reality.

“I like to think of my work as conceptual,” James says. “I like work that’s completely staged but looks totally natural.”

His vision and his sense of light is influenced by the photographers he admires, Richard Avedon, Helmut Newton, Albert Watson and particularly David LaChapelle, whose elaborately choreographed, apparently random and violently colourful images were the toast of magazines at the turn of the century.

James will sometimes sketch out his approach to a particular image before letting things evolve in front of his lens.

“I want to get it right in front of the camera,” he says.

“I don’t want to shoot 200 images, I want to get it in 35 or 50 photos, just the way I did with film. I don’t spend much time on my personal work in Photoshop. I don’t fix wrinkles and blemishes, I celebrate them.”

Download a PDF of the published pages for this story here.

Originally published in in the Sunday Guardian Arts Magazine for January 05, 2014

Marlon James reviews a capture of Alex Girvan during a shoot at a Duke Street car park on December 20. Photograph by Mark Lyndersay

“I’ve never felt like I belonged in the Caribbean,” says photographer Marlon James as we walk briskly up Henry Street in Port of Spain.

This is how the Jamaican photographer and artist has been experiencing much of Trinidad and Tobago since he moved here in January.

Strolling and striding his way through much of his measured and introspective interaction with a new landscape and people.

Much of his photography over the last ten years in Jamaica has been a search for his identity as a young man in the region.

On an overcast evening walking up a distinctly gray street under a brooding sky, Marlon James is again engaged in that exercise. We cut a quite ordinary profile as a group, distinguished only by our fast pace.

James is wearing jeans, and a white t-shirt and one hell of an equipment load in his worn backpack, his subject, architect Alex Girvan is all spiky dreads, jeans and a long gray coat that makes him look like more of a factory floor supervisor than a Matrix wannabe.

James is looking for a particular parking lot in the city that has old stone walls painted white, but we find the gate firmly locked. The rain is a menacing sprinkle now, and the light is disappearing.

A block further along on Duke Street we find another lot with a promising wall and a dour security guard. James ducks in quickly and flashes a charming smile and asks permission to use the spot for his photo.

He quickly sets up a tripod, wrestles with a slack ball-head and begins directing his subject through a series of poses inspired by his observation of Girvan’s gestures movements.

James’ style is disarmingly simple. He gets in close with a radio controlled handheld flash, gesturing and coaxing Girvan who has a flair for the moody pose while urging his subject to look into the lens and not at him.

“People tell me that my subjects tend to be a bit...well-to-do,” James notes after we part company with Girvan.

It isn’t surprising, given that James’ parents were bankers and he grew up in Jamaica as an “Uptown” boy, someone who had a full and paid education, whose family could fly out of the island regularly.

“I was really more middle-class,” he admits with a shrug.

Those professional parents proved to be supportive of their creative son, even more so when he began to get recognition for his work.

At 33, he’s comfortable admitting that his mother got him his gear when he made the shift from sculpture to photography, a change he acknowledges came because of the lure of the ‘instant gratification’of the medium.

When he made that decision, instant meant something else entirely in photography.

“I could process a roll of film and go into the darkroom to develop it,” James said.

“My sculpture would take weeks to take shape. I fell in love with the darkroom.”

He got serious with photography in 2003, but his first big break came in 2008 when he shot for Red Bull, then shortly after that for Red Stripe. James was also building a collection of portraits of people in the arts community in Jamaica when he began hearing that his prospects as an artist might significantly improve in T&T.

But it wasn’t until he started meeting people in the Trinidad arts community after moving here that he began to consider pursuing his portrait project locally.

He started a couple of projects soon after arriving, at least one sparked by the thriving night life in the city that he calls Night Shift, photographs of vendors working late at night.

Marlon James has been doing some commercial work while he works his way through these projects, shooting for advertising agencies and magazines.

“The work that I’ve been getting has been able to sustain me,” he said.

“In Jamaica, I’d have to have a nine to five job and probably some side jobs. Some of the work has been hard and fast, but some of it has offered creative freedom and I’ve appreciated that.”

In March 2014 he’ll find out whether moving to T&T was the right move for him as an artist with work to show and sell. Along with group shows in Holland and Washington, he plans a solo show in Trinidad.

“You can’t sell your work in Jamaica for what you’d get for it internationally,” he says.

“Except for a few collectors, the economy just won’t support those prices.”

Whether or not things work out financially, James has been greatly heartened by his experiences in Trinidad over his first year.

He admits to being lonely some of the time and hasn’t gathered the circle of friends and support he had in Jamaica, but appreciates the willingness of local artists to talk and collaborate.

James is particularly hopeful about the possibility of working with Melissa Matthews, a recently returned multimedia artist on a project.

Most striking for the photographer who does much of his work with subjects in their environment has been the way he has been received.

“People are more accepting of the presence of a photographer here, I’ve found.”

Marlon James is known as a portrait photographer, much of his previous work cleanly isolating his subjects from their backgrounds and focusing on still, patient engagements with the lens.

The theatre in his work plays out behind the expressions of his subjects, raising questions about the interplay between photographer and subject, emotional context and reality.

“I like to think of my work as conceptual,” James says. “I like work that’s completely staged but looks totally natural.”

His vision and his sense of light is influenced by the photographers he admires, Richard Avedon, Helmut Newton, Albert Watson and particularly David LaChapelle, whose elaborately choreographed, apparently random and violently colourful images were the toast of magazines at the turn of the century.

James will sometimes sketch out his approach to a particular image before letting things evolve in front of his lens.

“I want to get it right in front of the camera,” he says.

“I don’t want to shoot 200 images, I want to get it in 35 or 50 photos, just the way I did with film. I don’t spend much time on my personal work in Photoshop. I don’t fix wrinkles and blemishes, I celebrate them.”

Download a PDF of the published pages for this story here.

blog comments powered by Disqus