A kinda legacy

14/10/14 10:33 Filed in: Review

A review of We Kind ah People by George Tang and Ray Funk originally published in the T&T Guardian on October 13, 2014

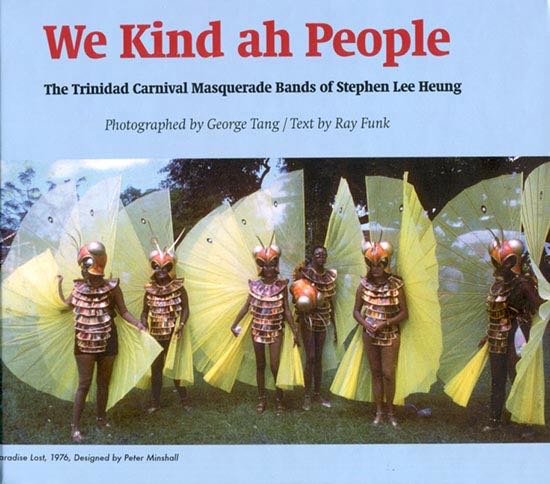

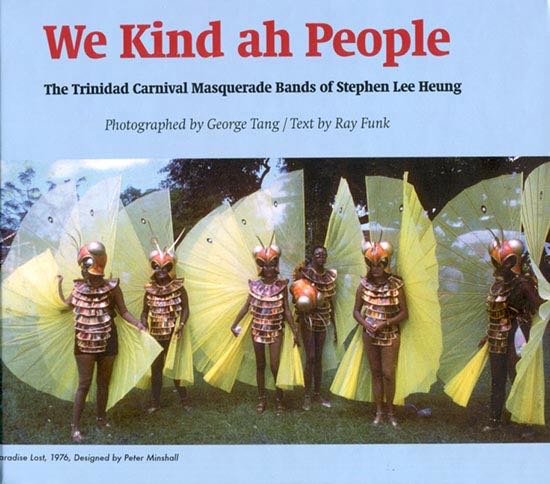

It’s hard to fault George Tang and Ray Funk for their ambitions here. We Kind ah People, a new book documenting ten of the bands of Stephen and Elsie Lee Heung is a first bold effort at placing the veteran masmaker in the pantheon of Carnival’s master bandleaders of the last century.

Of the 36 bands placed on the roads of Port-Of-Spain by the Lee Heungs over 50 years between 1946 and 1996, this book offers less than a third.

But the ten bands documented in the book offer a rich look at the craft of the Lee Heungs that we haven’t had before.

The bands, Terra Firma (1974), We Kind ah People (1975), Paradise Lost (1976), Cosmic Aura (1977), Love Is (1978), Hocus Pocus (1979), Cocoyea Village (1987), Columbus (1992), Safari (1993) and Festivals (1994) offer up designs by Carlisle Chang, Peter Minshall, Norris Eustace and Wayne Berkeley all engineered by the Lee Heung’s remarkably consistent production style.

Despite widely differing designs, there is a surprising unity among the bands, sound craftsmanship interpreting the sketches of the designers in an era that predated costume prototypes at band launches.

That process crafted bands from quite diverse designers that were stylish and precise as well as sensibly and economically executed.

The book doesn’t explain the gaps in coverage, noting only that “George was not able to take photographs every year,” but also acknowledging that they were largely taken “for his family and friends in the band.”

Fortunately, Tang was a craftsman who understood the limits of his medium and worked effectively within them.

What isn’t written into the book’s record is the monumental effort that has been invested in this work or the very different photographic circumstances under which the images were captured.

Most of these images, if not all, were shot on colour transparency film, a medium that dramatises the contrasty extremes of bright Caribbean sun.

In many of the images, the faces and expressions of the masqueraders disappear beneath their costumes, identities swallowed in the shadows cast by grand flourishes of their designers.

George Tang’s camera records no other photographers, since in the Carnival he photographed, far fewer photographers roamed the streets and all respected the asphalt stage on which masqueraders performed.

In this era, each photograph was metered, every frame had to be bought and processed. A photographer operating on his own capturing the festival did so not only with his own dollar, but often with a budget.

There must have been wining, but Tang’s record of the time shows masqueraders chipping along, surging as they hit the stage and doing that curious thing once called playing their mas.

The photographs, like the man, are direct but unassuming. They confront the spectacle before them with casual ease, recording with clarity a collection of costumes that have largely disappeared from the public consciousness.

From the brilliant, often abstract fancies of Carlisle Chang to Minshall’s diaphnous Grand Guignol to the burlesque design abandon of Wayne Berkeley, the book offers for consideration a Carnival that will be undeniably alien to today’s masqueraders.

In the 18 years since Stephen Lee Heung last brought a band to the streets of Port-of-Spain, so much has changed in both the public record of the festival and in the costuming of Carnival that it’s almost impossible to recognise any evolutionary link between the festival of today and the event that the photographer recorded between 1974 and 1994.

It’s possible to look at the glistening, angular brilliance of Carlisle Chang’s Terra Firma and the rococo styling and shiny piping of Folette Eustace’s Festivals and not be surprised, but anyone who looks at this record after being indoctrinated by the modern record of Carnival is going to be stunned.

Twenty years separate those bands, but they are clearly kin. In the 18 years since, everything seems to have changed about the costumes, the masqueraders and the very idea of a band when compared with this record of Carnival.

As a photographer, Tang’s work takes a qualitative jump forward between 1977 and 1978. The earlier images have the casual flow of snapshots but then the documentarian seems to decide that his work is a record of something special and his attentiveness to the specifics of the work intensify accordingly.

His shooting positions are more compellingly aligned with the position of the sun and his interactions with the band’s masqueraders are more deliberate and considered.

His shooting positions are more compellingly aligned with the position of the sun and his interactions with the band’s masqueraders are more deliberate and considered.

In one remarkable photograph, designer Stephen Sheppard, playing Alladin in Hocus Pocus, appears to glide along the roadway on his magic carpet, the roadside onlookers subtly blurred as he appears to speed by.

In another, a sexy showgirl in a tuxedo top with glorious legs in black stockings leads her section down Ariapita Avenue.

In this book, George Tang has captured a remarkable era of Carnival, the last era of massive costumes, capes, standards and headgear and yes, even cocoyea as the principal decoration of a band.

Writer Ray Funk works hard to craft a context for the work, writing informative chapter openers for each of the band and contributing an extensive history of both the photographer and the bandleader at the end of the book.

It’s a exhaustive effort to offer a context for the other 26 Lee Heung Carnival productions, but it’s also a reminder of just how much has been lost over the years through institutional disinterest in the visual history of the festival.

Funk writes well and engagingly, but the text could have done with some professional oversight and a copyeditor’s pruning, the occasional error a disturbing hiccup and the writer’s love fest with the sheer enormity of the Lee Heung legacy called for more grit and less helium.

The restoration work on the images is also somewhat, um, spotty, with several images in need of professional toning adjustment and crud on the originals needing removal.

Still, there’s no denying that where there was nothing, there is now something. Mr Funk and Mr Tang have sacrificed a great deal to produce this document and as a self-published Blurb book, it is likely to be both costly to reproduce and rare in number.

Serious Carnival aficionados should budget for the project, because it is very much a labour of love and one that’s likely to be in demand among the Carnival savvy.

It’s hard to fault George Tang and Ray Funk for their ambitions here. We Kind ah People, a new book documenting ten of the bands of Stephen and Elsie Lee Heung is a first bold effort at placing the veteran masmaker in the pantheon of Carnival’s master bandleaders of the last century.

Of the 36 bands placed on the roads of Port-Of-Spain by the Lee Heungs over 50 years between 1946 and 1996, this book offers less than a third.

But the ten bands documented in the book offer a rich look at the craft of the Lee Heungs that we haven’t had before.

The bands, Terra Firma (1974), We Kind ah People (1975), Paradise Lost (1976), Cosmic Aura (1977), Love Is (1978), Hocus Pocus (1979), Cocoyea Village (1987), Columbus (1992), Safari (1993) and Festivals (1994) offer up designs by Carlisle Chang, Peter Minshall, Norris Eustace and Wayne Berkeley all engineered by the Lee Heung’s remarkably consistent production style.

Despite widely differing designs, there is a surprising unity among the bands, sound craftsmanship interpreting the sketches of the designers in an era that predated costume prototypes at band launches.

That process crafted bands from quite diverse designers that were stylish and precise as well as sensibly and economically executed.

The book doesn’t explain the gaps in coverage, noting only that “George was not able to take photographs every year,” but also acknowledging that they were largely taken “for his family and friends in the band.”

Fortunately, Tang was a craftsman who understood the limits of his medium and worked effectively within them.

What isn’t written into the book’s record is the monumental effort that has been invested in this work or the very different photographic circumstances under which the images were captured.

Most of these images, if not all, were shot on colour transparency film, a medium that dramatises the contrasty extremes of bright Caribbean sun.

In many of the images, the faces and expressions of the masqueraders disappear beneath their costumes, identities swallowed in the shadows cast by grand flourishes of their designers.

George Tang’s camera records no other photographers, since in the Carnival he photographed, far fewer photographers roamed the streets and all respected the asphalt stage on which masqueraders performed.

In this era, each photograph was metered, every frame had to be bought and processed. A photographer operating on his own capturing the festival did so not only with his own dollar, but often with a budget.

There must have been wining, but Tang’s record of the time shows masqueraders chipping along, surging as they hit the stage and doing that curious thing once called playing their mas.

The photographs, like the man, are direct but unassuming. They confront the spectacle before them with casual ease, recording with clarity a collection of costumes that have largely disappeared from the public consciousness.

From the brilliant, often abstract fancies of Carlisle Chang to Minshall’s diaphnous Grand Guignol to the burlesque design abandon of Wayne Berkeley, the book offers for consideration a Carnival that will be undeniably alien to today’s masqueraders.

In the 18 years since Stephen Lee Heung last brought a band to the streets of Port-of-Spain, so much has changed in both the public record of the festival and in the costuming of Carnival that it’s almost impossible to recognise any evolutionary link between the festival of today and the event that the photographer recorded between 1974 and 1994.

It’s possible to look at the glistening, angular brilliance of Carlisle Chang’s Terra Firma and the rococo styling and shiny piping of Folette Eustace’s Festivals and not be surprised, but anyone who looks at this record after being indoctrinated by the modern record of Carnival is going to be stunned.

Twenty years separate those bands, but they are clearly kin. In the 18 years since, everything seems to have changed about the costumes, the masqueraders and the very idea of a band when compared with this record of Carnival.

As a photographer, Tang’s work takes a qualitative jump forward between 1977 and 1978. The earlier images have the casual flow of snapshots but then the documentarian seems to decide that his work is a record of something special and his attentiveness to the specifics of the work intensify accordingly.

In one remarkable photograph, designer Stephen Sheppard, playing Alladin in Hocus Pocus, appears to glide along the roadway on his magic carpet, the roadside onlookers subtly blurred as he appears to speed by.

In another, a sexy showgirl in a tuxedo top with glorious legs in black stockings leads her section down Ariapita Avenue.

In this book, George Tang has captured a remarkable era of Carnival, the last era of massive costumes, capes, standards and headgear and yes, even cocoyea as the principal decoration of a band.

Writer Ray Funk works hard to craft a context for the work, writing informative chapter openers for each of the band and contributing an extensive history of both the photographer and the bandleader at the end of the book.

It’s a exhaustive effort to offer a context for the other 26 Lee Heung Carnival productions, but it’s also a reminder of just how much has been lost over the years through institutional disinterest in the visual history of the festival.

Funk writes well and engagingly, but the text could have done with some professional oversight and a copyeditor’s pruning, the occasional error a disturbing hiccup and the writer’s love fest with the sheer enormity of the Lee Heung legacy called for more grit and less helium.

The restoration work on the images is also somewhat, um, spotty, with several images in need of professional toning adjustment and crud on the originals needing removal.

Still, there’s no denying that where there was nothing, there is now something. Mr Funk and Mr Tang have sacrificed a great deal to produce this document and as a self-published Blurb book, it is likely to be both costly to reproduce and rare in number.

Serious Carnival aficionados should budget for the project, because it is very much a labour of love and one that’s likely to be in demand among the Carnival savvy.

blog comments powered by Disqus